Girl Asks Mom to Diaper Hr Again

'Am I Even Fit To Exist a Mom?' Diaper Need Is an Invisible Office of Poverty in America

iStock.com/SolStock

Connecting state and local government leaders

Parents cannot use federal help to pay for diapers, and are often forced to come upwards with other solutions, using maxi pads or towels to proceed their children clean and dry. In rural America where aid is even harder to access, tiny diaper banks are the merely lifeline.

Originally published past The 19th.

SPRINGFIELD, MO — The minivan leaves Springfield before the sun hits the limestone outcroppings of the Ozark Mountains, zipping past church-dotted roads and winding this way and that — deep, deep, deep into the hills. In its trunk are nearly a dozen boxes of Cuties and Huggies, sizes four and 5.

A scattering of cars are already queued upwardly when the van pulls into an otherwise empty shopping center — with a tiny, blink-and-you'll-miss-information technology food pantry — in Forsyth, a town of most 2,500.

Kelly Brown unloads the boxes, her eyes on the cars in the line. Most are seniors coming for food — "I don't need diapers, even so!" — but then she spots a child. About a quarter of children in this region live in poverty, and their parents, most of whom are working, can't cover the toll of diapers — nearly $100 a month. In the dorsum of Angela Colley's Ford Excursion is her three-yr-sometime girl in a booster chair. Brownish premises upward to Colley's window.

"Do you demand whatever diapers for your kiddos?" she asks, wearing a black T-shirt that reads, "This shirt doubles every bit a cloth diaper."

Colley's eyebrows shoot direct upwards. Yes, she says, surprised. Brown quickly looks through their stores for a 74-pack of GoodNite pull-ups and stows it in Colley's backseat. She hands the petty girl a small stuffed cat.

Colley is at the nutrient pantry to pick upwards nutrient for her family of seven. She said she didn't know she could also get diapers for free. Her iii-year-old isn't fully potty trained just yet, and affordable pull-ups have been nearly impossible to find since the pandemic began. When she can't, she's washed what she must: slapped a maxi pad onto toddler panties and prayed it could keep her girl comfy for at to the lowest degree a couple hours.

Colley has v children — ages 18, x, nine, 8 and 3 — and she remembers a time when three of them were in diapers at in one case, running through as many as ten to 12 a day each. At present, a pack will hold her girl through the week, only in those days, the need for diapers brought her to her knees.

Their family wasn't always struggling financially. Colley's hubby lost his chore equally a truck driver due to a health condition during the Great Recession. The family unit was evicted and became homeless. Her kids were just babies so. They could get food and clothes at a pantry or with nutrient stamps, but diapers were a unlike story. So she began asking strangers for money to buy them.

(Click to expand the photos for explanation data.)

"You lot weep — it'due south very humbling to have to inquire strangers for coin for diapers," Colley said.

Once, she gathered upwardly all her silver jewelry, gifts from her family, and pawned it for $20 — enough to buy one big pack of Luvs. Some other fourth dimension, she found a pack of diapers for $eight at a thrift store, just all she could scrounge together in her car was $v in change. She wept when she asked for a $3 discount that was denied. Later, she wrapped a towel around her child instead.

Diapers have rattled Colley's conviction, sending her thoughts racing when her need was greatest: Am I even fit to be a mom? What if I don't deserve these kids? Will my children get taken away from me?

Nationwide, studies have plant that diaper need is a greater correspondent to postpartum depression than food insecurity and housing instability. A landmark 2013 study in Pediatrics, a peer-reviewed medical periodical, was the commencement to quantify the psychological trauma diaper demand has on parents, some who reported leaving their children in soiled diapers for extended periods when they couldn't detect any, leading to urinary tract infections and diaper rash. Other parents skipped meals to pay for diapers. Almost ever, mothers suffer the greatest impact.

"Considering women are much more likely to be encumbered by poverty … it becomes an outcome that is not gender neutral," said Megan Smith, the lead researcher in the Pediatrics study. "[Diaper need] was really merely all-consuming for the mothers we talked to."

During the pandemic, the toll of diapers ballooned well-nigh 14 percent on average, according to a Nielsen written report. At the Family Dollar months agone, a pack was $ix, Colley said. Now it's $11. She spends $44 a calendar month on pull-ups, even for a kid who is nearly 100 percent potty trained.

The frustration over diapers has given mode to anger more times than Colley can count. The questions from others are almost always the aforementioned: Why did she have kids, if she couldn't afford the diapers? Her family was doing OK when they had their older children, and so OK over again when her 3-year-old was born. Merely poverty is non an identity — it'southward a country, 1 you can move in and out of.

The inability to provide diapers is a silent struggle in this country. Different with food and clothes, diapers cannot be rationed or modified — the option is a disposable diaper or a cloth ane, an expense that doesn't qualify for federal aid under nigh public help programs, including food stamps.

That'south where organizations like the Diaper Bank of the Ozarks step in.

Welfare reform in the mid-1990s eliminated the cash help program the bulk of low-income families relied on and replaced it with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), a program that less than a quarter of depression-income families tin can now admission. Shortly after, in the early 2000s, diaper banks — which collect diapers and distribute them to families in need for free — started popping up. The National Diaper Bank Network was created to help back up banks across the country in 2011, around the same time the Diaper Bank of the Ozarks was founded by Jill Bright, a retired British nurse who learned about diaper demand at a conference and brought the concept back to Springfield.

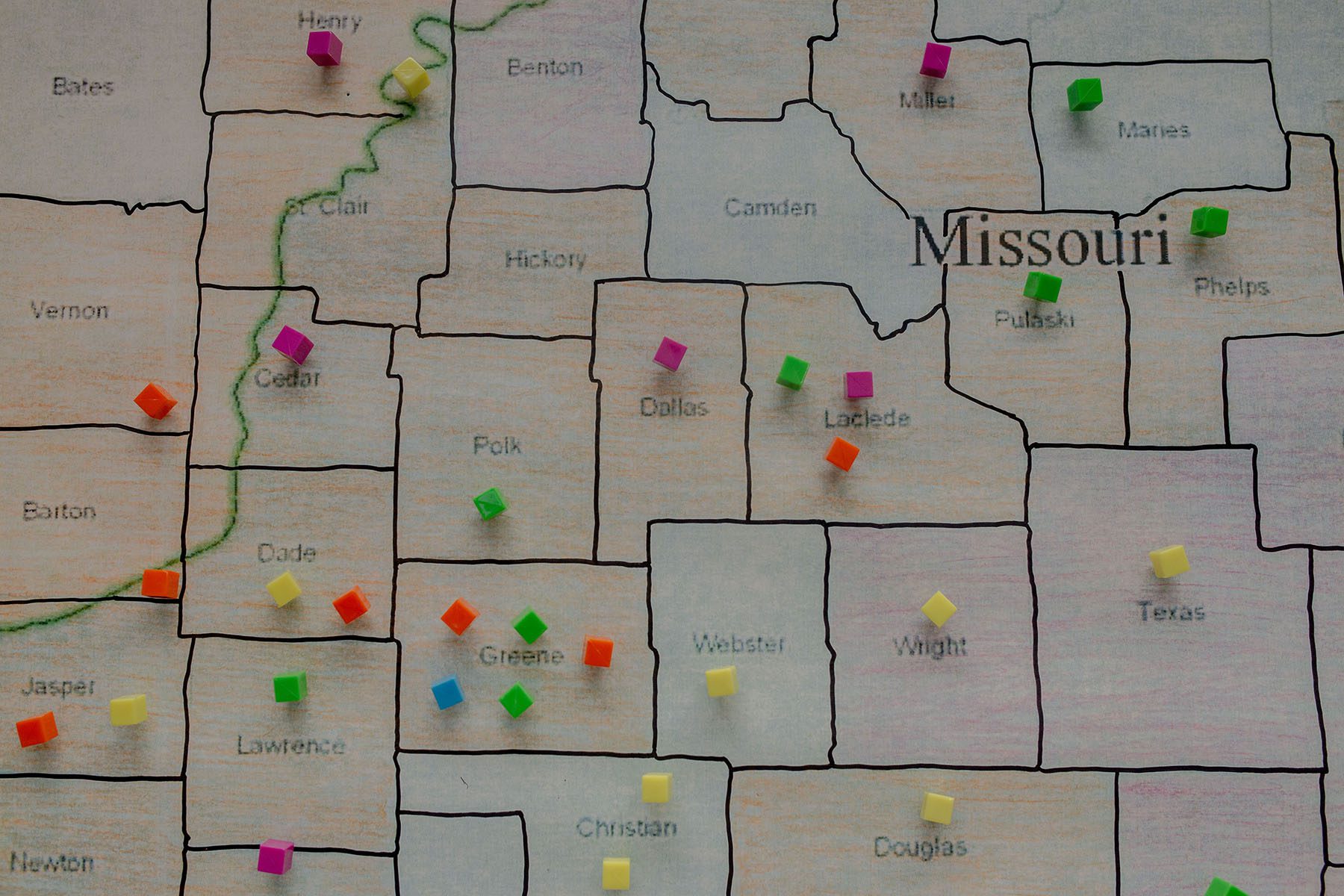

The bank started out in a closet of another nonprofit, with merely seven partner agencies, distributing 50,000 diapers the offset year. And then it exploded. For the first couple of years, distribution doubled annually. In 2021, it's on track to distribute 1.2 1000000 diapers through 105 partner agencies, covering one of the largest areas of whatever banking company in the land — 50,000 square miles beyond 50 counties in the Ozarks — a region mostly made up of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas — into communities with simply a couple hundred residents. It is the model for rural diaper bank distribution.

And yet, "it's not practiced enough," said Kelly Paparella, the bank's assistant executive director who, along with Chocolate-brown, represent the 2 paid staffers at the Diaper Banking concern of the Ozarks (both named Kelly). "Nosotros're really looking at the gaps — who are the people who really need the services? — considering nosotros know that there's inequities."

But, so far, the public and political volition has not been there to address it, and banks like the one in Missouri go on to string together a grassroots effort to attain into the poorest pockets of the land with barely enough resources to even get there.

The Diaper Bank of the Ozarks recently completed a study to see how many diapers it could distribute to see merely the supplemental need among low-income children in their region. The number wasn't the 1.two million they'll distribute this year, an all-time high — not even close.

It was 27 meg.

After the distribution in Forsyth, the Kellys hop back into their van and nautical chart a form into the mountains toward Branson, a tourist town about xxx minutes away, known for its profusion of theaters, motels and family-style amusements — mini-golf courses, zip lines, thematic museums.

At another food pantry run by a Christian organization, the line of cars is already a half dozen deep as the van pulls in, long before the distribution is ready to beginning. They get automobile past automobile, asking if anyone needs diapers for their kids — or their grandkids. Meth addiction has price many children their parents hither. About 20 percent of the people the Ozarks diaper banking company helps are grandparents on a stock-still income caring for grandchildren.

Dark-brown and Paparella meet Heather Reeves, a grandmother of 3 children under three, who can't beget diapers with the income she gets from her disability payments. She relies on the banking concern to pick upwardly diapers twice a month.

They give a couple of packs of diapers to Sommer Guthrie and her fellow, Colby Ball, who stop by every month for their 3-year-onetime. Ball works at LongHorn Steakhouse and they live in a hotel with a roommate. Guthrie has tried to look for work, only the pay wouldn't be enough to cover twenty-four hours care. When her son was a infant, she asked the folks at the food pantry if they had diapers, and to her surprise, they did. She'southward been coming dorsum consistently since.

When the Kellys offer diapers to parents or grandparents, they tin can see the relief on their faces. That moment is why they depict this work as their calling.

"I found a office in my piece to exist able to tackle poverty considering I, as well, was just completely dumbfounded [when I learned nigh diaper demand]," Paparella said. "Anybody knows diapers are expensive. Nosotros joke nigh it: You're pregnant and immediately the get-go thing was, 'Oh wait 'til you have to buy diapers.'"

Oftentimes to the surprise of parents, assistance programs, like nutrient stamps or WIC, the supplemental programme for low-income women and children, cannot be used to buy diapers. Both are nutritional assist programs, and diapers don't qualify because they are considered a hygiene product. Medicaid won't cover them unless a doc deems them "medically necessary" to treat a specific ailment similar diaper rash, which tin can arise from parents not having enough diapers in the commencement identify.

But TANF provides greenbacks assistance for low-income families that could conceivably be used to purchase diapers. But TANF is hard to utilise or qualify for, and it'southward increasingly shrinking — in Missouri, only well-nigh ix percent of the state's TANF funds are spent on cash assistance for families.

And and then consider the poverty tax: Diapers, when bought in bulk, are significantly cheaper per unit, only to exercise that, families take to spend more than upfront, or have a membership to a big-box retailer like Costco. A single diaper may cost about $1.50, only in bulk the cost tin drop to as lilliputian every bit a quarter per unit of measurement, said Kelley Massengale, the researcher who led the study in Due north Carolina.

The event of that inability to purchase diapers in majority shows upwards in simply how much diapers soak up in a low-income family unit's budget. The poorest 20 percent of families in the land spent nigh 14 percent of their household income in 2014 on diapers, according to an analysis by the Center for Economical and Policy Research. For middle-income families, diapers absorbed about just iii percent of their income.

That reality, though, is hard to convey in southwest Missouri, where the concept of giving abroad diapers for free is often met with questions about why parents aren't "just" doing cloth instead, or why the parents aren't working, why they had a child if they couldn't afford the diapers.

Laura Mowery, who heads ane of the Ozark bank's partner agencies, a mobile unit of measurement that carries diapers to rural towns, said the struggles low-income families endure have been oversimplified to the indicate that some people internalize beliefs about what families should be able to do. She did information technology herself at first when her church asked for diaper donations.

"I myself swept it nether the carpet because I idea, 'I'm not ownership diapers. If yous want them, go to work,'" Mowery said. "But let'southward say you do take a kid and y'all are working — you're working every day — just you lot have to pay your rent, and your utilities. Where'south your food money? Where's your diapers? People actually demand to empathise at that place'southward more than just, 'Get a job' for these parents."

Two-thirds of families experiencing diaper demand are employed. Some of them can't work considering, without diapers, they can't put their children in child care. Day cares typically alter children'due south diapers every ii hours, and parents are expected to provide enough diapers up front to last the twenty-four hour period. A 2017 written report of diaper bank recipients in North Carolina found that 7 per centum said they had to miss piece of work because of diaper need. When diapers were provided to those families, xv percent of parents reported it immune them to render to work or schoolhouse and 18 pct said information technology allowed them to put their children in child care.

The Ozarks diaper depository financial institution provides diapers to child intendance centers to have on mitt in case a parent doesn't have the necessary corporeality. Paparella said they realized parents weren't irresolute their kids at home to ensure they could still go. One day care center would put a Sharpie mark on infants' concluding diaper change of the day, and sometimes, that same diaper came dorsum the next morning.

The depository financial institution's material program, which Paparella leads and will talk about for hours if you lot become her started, too helps provide crucial services for parents. Textile diapers, while reusable, can run from a couple dollars to $30 each, and parents need about two dozen. The banking concern gives parents all the material diapers they will demand for free through the time their child is potty trained, eliminating the loftier cost barrier.

Paparella runs a class at the depository financial institution educating near the price savings in the long run with cloth diapers and the best ways to launder them (you lot can't use softener, for i). The bank estimates that the 64 cloth diaper kits it gave out last year equate to nearly 600,000 dispensable diaper changes. But fabric isn't for everyone: Some laundry facilities and day cares won't have them, and they are difficult to send on public transit if you don't have a auto or a washer and dryer at home.

The Ozarks banking company has tried to provide this education and expand equally far as it can with the picayune resources information technology has. The get-go year Paparella joined the depository financial institution, for example, in 2017, it was serving 15 counties. And so 30 counties the next yr. Now 65. Out here, where towns are far apart and nigh families however don't know the diaper bank exists, their work is hard. Most of the parents they saw on their trip to Forsyth and Branson were learning that diapers were bachelor at the food pantries for the first time.

"Merely like it takes a village to raise a kid, it takes all of the collaborations of organizations and agencies in those communities to reach families," Dark-brown said. "Some of our partners travel 4 hours i-manner to come get diapers, so we are dependent on them to carry out that mission in their community."

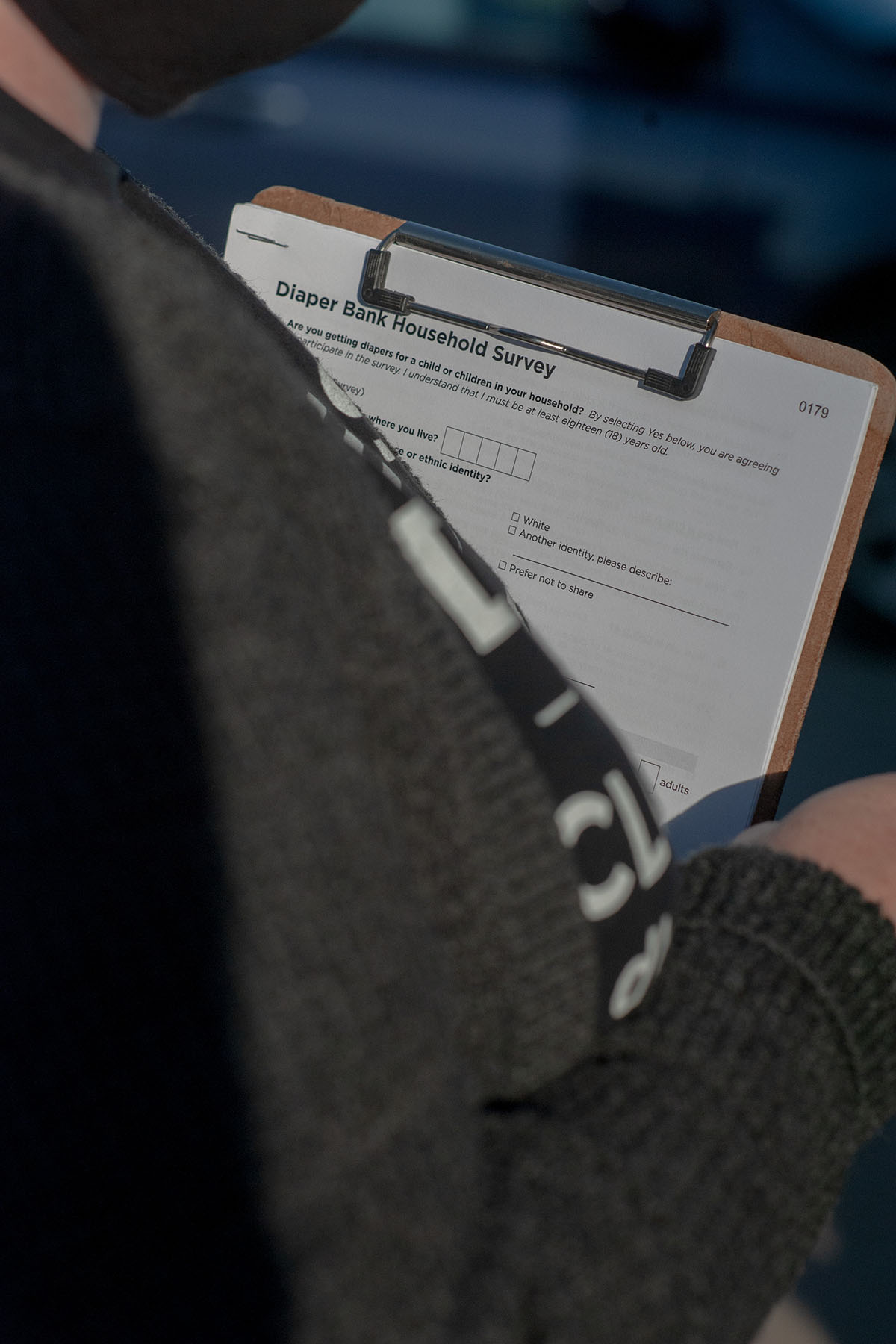

Inquiry on diapers is nevertheless in its nascent stages, but Massengale is helping conduct a nationwide study of diaper demand with the aid of lx diaper banks, including the one in the Ozarks, surveying equally many as 11,000 families.

The data could pave the road for more policy, showing that "whenever in that location is a diaper bank in a community, it's helping to meet this basic homo need for families," Massengale said. "It's likewise saving our health care system dollars, information technology's providing access to early childhood instruction, it'south keeping families in the workforce."

Just currently, diaper need has been met with all but indifference while more and more than families written report struggling to even have enough food for their children. There has been, withal, a precipitous rising in policy that supporters merits protects children.

In the past year, more than states have enacted laws restricting ballgame in 2021 than any other fourth dimension in American history. Subsequently Texas, where a new constabulary all simply eliminates ballgame access, Missouri's patchwork of regulations is considered among the harshest in the land.

Many people specifically cite their inability to sustain their families financially every bit part of the reason they seek out abortions. And however, there is far less impassioned give-and-take about what needs to happen to support families after a child is built-in.

Joanne Goldblum, the CEO of the National Diaper Banking concern Network — which now counts more than than 225 members — estimates demand for diapers has grown 86 per centum during the pandemic. Nationwide some diaper banks reported doubling their distribution; At 1 of the Ozark bank'southward partner agencies in Ash Grove, a boondocks of i,400 a half hour outside Springfield, the number of families needing diapers has doubled, said Pattie Moulin, who runs the diaper pantry from the town'south United Methodist Presbyterian Church. Before March 2020 they were serving maybe 17 or eighteen local families — at present it'southward 40.

The standoff of those 2 things — a rise in poverty while abortion admission shrinks — incites a complicated question about American credo: Does the sanctity of life cease after those first cries if, in do, the The states fails to support children once they are out of the womb? In rural areas, where abortion is largely decried but aid is necessary, it gets even muddier.

"We're very pro-life [in this region]," Paparella said. "You want to protect the unborn baby, but we demand to protect the baby that's born afterwards."

Colley, the mom of five, is religious and doesn't support abortion, but she can understand why someone would get one.

"You just gotta understand how difficult information technology is for people to heighten children in this earth these days with no support," she said. "If we're making anti-abortion laws, we need to support the children that are here more."

Yet, there has been almost no concrete activeness on diaper need at the federal level, despite a handful of bills that accept been proposed to shuttle assist to diaper banks. Information technology's low-hanging fruit, advocates fence, that could help significantly reduce diaper need in the country. Virtually banks, like the 1 in the Ozarks, are run nearly entirely by volunteers, who are led by a few paid employees and a budget of a couple hundred thousand dollars a twelvemonth.

Meanwhile, the need is neither new nor diminishing. It's a window into poverty, Goldblum said.

"I know that diapers are not the answer to ending homelessness, but sometimes diapers can be the departure for 1 family," she said. "I think that'due south what's powerful nigh this — we are talking about basic human nobility. Nosotros're non talking about complicated issues."

There were moments in the pandemic when diaper need of a sudden shot upwards to national prominence. Major publications carried stories nigh the cost of diapers rising; virtually big-box retailers running out of supplies; about a dad stealing a box for his kids, drawing a crackdown from his local police force department and an outpouring of back up from parents who came to his defense force. It's the kind of moment-in-time focus that also happened afterward the Bully Recession, when President Barack Obama called for ending diaper need.

This yr, 2 bipartisan bills emerged, the commencement time Republicans have cosponsored legislation.

Republican Sen. Joni Ernst cosponsored a nib with Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy that would provide $200 one thousand thousand in aid to diaper banks as a outcome of the pandemic. Republican Sen. Kevin Cramer joined Sen. Tammy Duckworth, a Democrat, in introducing companion legislation in the Senate to the Stop Diaper Need Human action, a bill Reps. Barbara Lee and Rosa DeLauro have been pushing in the House for years. It would provide ongoing help to diaper banks — $200 meg a year through 2025 — as well as qualify diapers for utilize with a wellness savings account, and allow Medicaid recipients to receive diapers for older children with a medical necessity.

All potential watershed moments, and then — zip. The bills sit in the record, unmoving. Perhaps in that location's still not enough bipartisan support, or political volition, or too many other priorities.

"This should be a lay-upwards," said Audrey Symes, a volunteer lobbyist for the National Diaper Bank Network. "Why is information technology not happening? It's not that expensive."

Goldblum has come upward against this reality endlessly in the 2 decades since she started a diaper bank in New Haven, Connecticut, one of the outset in the country. Two decades of advancement have turned upwards a scattering of legislators willing to accept on the cause, a couple proposed bills, some motion in some states, simply non much else. Often, she is still explaining diaper need to people for the first time.

"Legislators tend to recollect well-nigh the large pic and the truth is nobody very much thinks almost the petty things," Goldblum said. "But something as small as a diaper — I've had people say, 'This to me can make the departure between being able to make ends meet at the finish of the calendar month.'"

Goldblum and the diaper banks have pushed for legislation that does not include diapers in nutrient stamps or WIC considering those are food help programs, they debate, that are already suffering from petty funding as information technology is. They don't want to see families weighing whether to utilise the coin to feed or diaper their child. Instead they want to see individual set asides (the proposed legislation would be funded through the existing Social Services Block Grant, instead).

But previous attempts at doing that take been mocked. The first federal bill addressing diaper need, introduced in 2011 past DeLauro, a Connecticut Democrat, proposed that the federal authorities distribute diapers through child care centers. Conservative radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh lambasted DeLauro's proposal as an example of "nanny-country" legislation that "gives a new meaning to the term 'pampering the poor.'" Limbaugh argued the bill also left out parents whose kids were not in solar day intendance.

Lee, the Democrat from California, has tried a couple dissimilar directions, proposing removing sales tax on diapers — something 10 states now do, including California — sending grants to diaper banks and allowing parents to pay for diapers using pre-revenue enhancement dollars in wellness savings accounts.

She said some of her fellow members of Congress have laughed at the idea, "They said, 'OK Barbara, diapers? Why diapers?'" Lee said. It'south the same people who passionately decry ballgame, and all the same diapers has non been able to drum upwardly the same attending, she said.

DeLauro knows this road well. This twelvemonth, legislation to expand the child tax credit to the poorest families, something she's been championing for decades with little bipartisan support until quite recently, finally passed. Parents have reported using the funds — upwards to $360 a month for the youngest children — for diapers.

Simply the kid tax credit expansion is currently just for a yr, and, besides, information technology'south not a targeted solution to diaper need, she said.

"People experience it's not a front-burner issue," DeLauro said. "With the kid tax credit, it wasn't opposition, simply it was indifference. That may be the example here."

In Branson, Kelly Paparella gets a telephone telephone call.

A mom in her cloth diaper program, Desiree Abbott, has merely been to the doc with her 10-month-old son and learned he's allergic to coconut oil, the replacement for diaper rash cream that Paparella suggests parents utilize with cloth diapers. (It'due south 1 of the chief ingredients in nigh creams, and information technology's meliorate for the diapers). She doesn't accept any disposable diapers for the baby.

Abbott is living in a hotel with her hubby, Steven Bryant, the baby and their 2-year-old.

"And so, the address, nosotros're gonna text it to you, OK?" Paparella tells her from outside the food pantry. "You can simply click it and get on over here, and you guys can get some food and diapers today."

Abbott is only 25, but she and Bryant, 26, have faced more adversity in the by couple of years than most people see in a lifetime.

When her eldest son was born, she worked iii jobs and cared for her sick granddad. She was only a teenager. Her son was eventually adopted past her uncle. Last year, when Abbott was seven weeks pregnant with her youngest, doctors found an infection in the os backside her left ear that caused fractional facial paralysis. As she underwent handling, she showed up to her task at McDonald'due south with a picc line in her arm.

"I can't not provide for my kids," Abbott said. She lost a job this yr as a housekeeper because she missed piece of work while her centre son was in the hospital battling severe pneumonia.

They tried textile diapers to salve some coin, and now even that isn't quite working

Earlier Abbott arrives, Paparella prepares herself. What luck, she tells Kelly Brown, that they happen to be in Branson on the same day. Simply her job is catchy — she isn't merely distributing diapers. Sometimes, she's acting equally the connective tissue and different forms of aid. Paparella wants to help parents be cocky-sufficient, and some of that means keeping them accountable, making sure they are reaching out for all the help that's available to them. That requires edifice trust.

She spots Abbott right away when her automobile pulls up to the line outside the pantry. Strapped to the top of her old carmine Nissan is a big blackness stroller. The 2 boys are in the back in their machine seats, wearing matching necktie-dye shorts and tank tops.

Later on volunteers pack the back seat quite literally to the roof of the motorcar with diapers and wipes, Bryant takes the boys out and to a nearby park while Paparella talks through options with Abbott.

They take 2 nights left in their hotel, and so they have to become somewhere else. Some people have suggested she get out the kids at Isabel's Business firm in Springfield, an emergency services shelter. But Abbott is worried it could cost her custody of the boys. It could signal she isn't fit to care for them.

Paparella too urges Abbott to get out the kids at Isabel's Business firm. It won't put her custody in jeopardy, she tells her.

"To put myself in your shoes," Paparella tells her, gently, "I would empathise completely, considering when I offset learned about that, I was like, 'Oh my goodness, how do yous build trust with somebody to allow your kids to be staying with them?' When you run into the staff and when you run across what'south going on in there, they desire and encourage you to want to come all the time. That's why I want you guys to move to Springfield."

Paparella has been trying to encourage them to motility out of rural Missouri, to where the assistance is more than concentrated, where she can reach them. She wants Abbott to be continued to every resource available, because "i matter I empathise, in everything that you lot've always said is, this is your life," Paparella tells her, motioning with her index finger at Abbott'due south family unit in the altitude.

Abbott and Bryant's lives are so clearly congenital around their children. It's purposeful: Bryant didn't abound up with his dad, and being a father felt like a calling for him long before he became one. When he and Abbott found out they were pregnant with their first child, he carried the positive pregnancy test in his pocket. On his left bicep is a tattoo that reads "Ohana." Family.

When they've had diapers, things are OK, they tin provide. When they haven't, they've fallen into periods of severe depression.

It's and so upsetting, Bryant struggles to find the words to depict it. "Information technology's emotional," Abbott says. "At that point, it makes me think, maybe my kids are better with someone else."

Diapers for them are a symbol of who they are as parents. Without them, who are they?

Source: https://www.route-fifty.com/health-human-services/2021/11/am-i-even-fit-be-mom-diaper-need-invisible-part-poverty-america/187049/

Post a Comment for "Girl Asks Mom to Diaper Hr Again"